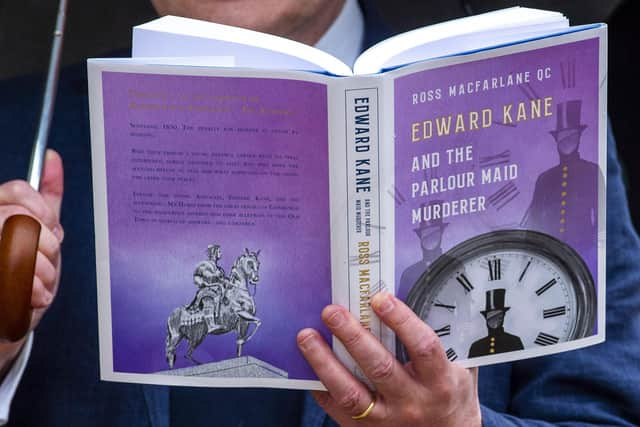

Edward Kane and the Parlour Maid Murderer, part one: The Hanging

It was generally agreed that the public execution of Charles Makepeace had provided excellent entertainment for the twenty thousand men, women and children who attended. On that day, the otherwise grey streets of Edinburgh had the atmosphere of a village fair where families and friends enjoyed a fine day out.In the middle of the crowd, Edward Kane Advocate, required to crane his neck to see the event. His manservant, ‘Horse’ (a nickname won at the Battle of Waterloo), stood beside him, holding Kane’s hat and gloves. This was the perfect spot from which to observe the hanging, except for the lady with the very tall hat directly in front of Kane.Kane pointed to Horse, then pointed to the lady before him. Horse leaned forward, his head almost resting on the lady’s shoulder. His thick Cockney accent cut through the otherwise Caledonian din: ‘Scuse me, my dear,’ he pointed to the offending piece of millinery, ‘would it be possible to remove the tile from the roof ?’The lady looked surprised by the request, then offended, then resigned. She began, with a great harrumphing, the extrication of a seemingly infinite number of pins. Horse made a slight bow to say: Thank’ee madam. The lady shook her head violently. The tresses, which until that point been restrained by her hat were now free to range left, right and upwards, leaving Edward Kane’s view now more restricted than before.

‘I fear, Mr Horse, that we have progressed from the inconvenient obstruction of the frying pan to the total eclipse of the fire.’‘Well, Mr K, I could always ask her to take off her ’ead...’Their exchange was interrupted by a loud murmur from the crowd. The murderer, Charles Makepeace, a.k.a. ‘Black Charlie’, was being led on to the scaffold. Makepeace scowled at the crowd, baring a mouthful of uneven teeth like a row of winter chimneys.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYes. Men of all degrees were standing for him now. Women of all ages watched, some with half-smiles on their faces, some breathless with the excitement of his end, some visibly praying for the repose of his not-quite-departed soul. Then there were the children in the crowd. Some dressed in their finery for the occasion, or asleep in their mothers’ arms, some excited now and looking in his direction. And there were those other children on the streets. Whose parents were still lying in drunken stupors in the hovels they called home. A life of petty crime would be their daily fight against starvation. The time-honoured techniques: the dipping of pockets, the three card trick, the rolling of the drunken gentleman. Makepeace smiled. The day of his death would be an anchor in the memories of others, a reference point in their personal almanacs: ‘It was around the time that Black Charlie danced on air,’ they would say. That memory, and only that, would be his lasting monument.

The trapdoor beneath Makepeace’s feet opened. For one so schooled in a lifetime of punishment and the constant threat of the noose, this development seemed to be a complete surprise to him. His eyes bulged in disbelief. The twisting and jerking fandango began, hands bound behind him punching against his lower back. The teeth grinding as if to resist the fatal pressure of his own body weight. The panicked cry as the irresistible wave of death washed over his gasps to reach the surface of life. And that dance, the dance on nothing but air. The dance on that open trapdoor, the void, Charles Makepeace’s personal doorway to Eternity.

After a few minutes, the dance was done. Charles Makepeace’s body at rest now and swinging and swaying gently at the end of a rope.All the while, Edward Kane, Advocate, had his eyes fixed to the ground - witnessing nothing of what would become an infamous demise.Mr Horse, on the other hand, was animated now: ‘Well, Mr K, I knows you’re squeamish and all, but you just missed a bloody good hanging. Time for a spot of luncheon, sir?’The entertainment over, some of the crowd began to pack their belongings and make their way back; others watched the body sway in the breeze.‘No, Mr Horse. You may return to your quarters. I shall visit Parliament House - and my box.’

Tomorrow: Part 2 The problem with ‘devilling’