Hell for Royal Scots on Japanese death ship

At first they were held in Hong Kong for several months but eventually it was decided that the PoWs were to be transferred to Japan where they would be put to work as forced labourers.

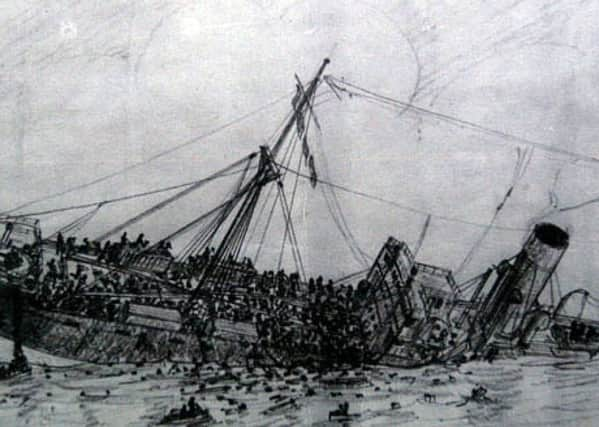

On September 27, 1942, the armed merchant ship Lisbon Maru sailed from Hong Kong. On board she had Japanese soldiers and around 1800 prisoners, who were crammed in to three separate holds. These included many local men from the 2nd Royal Scots. Crucially, and contrary to the Geneva Convention, she had no markings whatsoever to indicate she was carrying Allied PoWs.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn October 1, the American submarine Grouper was on patrol. A ship came into view. It was the Lisbon Maru. Lt Commander Duke sounded ‘General Quarters’ and his men sprang into action.

Duke decided that the moon was too light to mount a surface attack and opted to wait for daybreak. About 6.30am the Royal Scots were roused from their sleep. Some decided to take advantage of the quietness to visit the latrines. Many of them were suffering badly from dysentery.

At 7.04am precisely Grouper fired three torpedoes – all of which missed. A fourth was fired and a loud explosion was heard.

Grouper came up to periscope depth and saw the Lisbon Maru, dead in the water and listing. She fired off a fifth torpedo which missed. Then a number of small shells landed around Grouper’s periscope.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn board the merchant ship, the Japanese went into a frenzy, screaming and shouting at the PoWs who were forced at bayonet point back into the hold.

The sick men lying on deck were picked up and thrown down into the hold. The American sub then fired a sixth torpedo and dived. Shortly afterwards there was a loud bang, which they assumed was the torpedo hitting home. Incredibly a Japanese gunner had fired at the torpedo and hit it. A miraculous shot.

What followed next is horrific. For seven hours the prisoners were confined below deck, the air becoming foul with the sheer numbers of men and inability of them to go to a toilet.

Around 7pm a Japanese officer ordered the hatches to be battened down and covered in tarpaulin. Below in complete darkness it was dawning on the PoWs what was happening. The ship was slowly sinking and they were being left to die. The men in the hold behind the Royal Scots confirmed that the ship was taking in water and that they were unable to pump the water out now as there was hardly any air left to breath.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy the following morning men began to die from asphyxiation and sickness. The ship was groaning and starting to list more noticeably. Captain Shigeru, the captain of the ship, requested permission to abandon ship. This was granted but he was ordered to leave the prisoners to perish and blame it on the Americans.

Colonel Stewart of the Royal Scots, gave an order to attempt escape. It was evident to everyone that if they did not get out soon they would drown. At 9am the ship gave a dreadful lurch and settled down by the stern, coming to rest on a sandbank.

The terrifying noise of the men drowning in No 3 hold could be heard clearly. Two Royal Scots officers managed to force a way to the deck up a rickety staircase. They were spotted by the Japanese, who opened fire on them, killing Lt Potter.

The Japanese were then taken off the ship leaving the prisoners to fend for themselves. Col Stewart ordered the frightened men to abandon ship and make for land. It was over three miles to the nearest island in dangerous currents. Many would not make it. Japanese ships were in the area, but they stood by watching the soldiers drown, or even worse still, tormented the men with ropes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite this, many men made it ashore helped by Chinese fishermen.

Days later Roll Call was called. Of the original 1816 prisoners, 846 had perished. Amongst the dead were L/Cpl Andrew Cornwall from Dalkeith, L/Cpl Peter Burnett from Easthouses, and Andrew Jeffrey from Penicuik. The survivors were transported to Japan, where sadly at least another 10 local lads were worked to death in the infamous Kobe and Amori work camps.