How Edinburgh helped elect Britain's first Labour government 100 years ago

The early weeks of the new year 100 years ago was a time of historic change –Britain was on the brink of having its first ever Labour government.

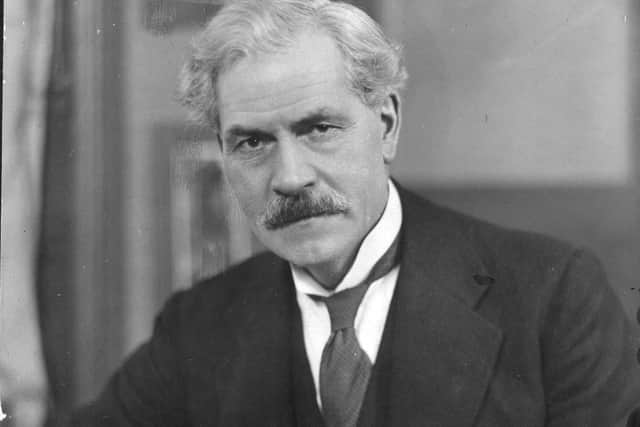

A general election on December 6, 1923, had produced stalemate at Westminster. which paved the way for Labour's Ramsay MacDonald to form a minority administration and become Britain's first Labour prime minister on January 22, 1924.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Tories had won a general election the year before on a manifesto committed to free trade, but prime minister Andrew Bonar Law had to resign due to ill health in May 1923 and with unemployment persistently high, his successor Stanley Baldwin wanted a mandate to introduce import tariffs, which he believed would help the economy.

But instead of confirming their comfortable majority, the 1923 election saw the Tories lose more than 80 seats and their overall majority disappeared, although they were still the biggest party with 258 seats. Both Labour and the Liberals increased their number of MPs. Labour was in second place with 191 seats – the biggest total since the party was formed in 1900 – and the Liberals had 158.

There could be no Tory-Liberal coalition, given their opposing views on free trade. And the Liberals did not want a coalition with Labour, but were ready to give them a chance to govern. Liberal leader Asquith argued: "If a Labour government is ever to be tried in this country, as it will be sooner or later, it could hardly be tried under safer conditions".

Labour recognised the inevitable constraints they would face without a majority and debated whether they should agree to form the government, but decided in the end they could not let the opportunity pass.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe party had been steadily increasing its parliamentary strength since winning its first two seats in 1900. But the biggest leap came in 1922 when the number of Labour MPs more than doubled across the UK from 63 to 142 – and in Scotland jumped from six to 29 – allowing them to replace the Liberals as the official opposition. The extra 16 they added in 1923 carried them into office as a minority government.

Labour had won its first seat in Edinburgh in 1918, at the end of the First World War, when councillor and journalist Willie Graham was elected in Edinburgh Central. The party won another two Lothian seats in 1922 – South Midlothian & Peebles and West Lothian, then called Linlithgowhsire – and a further two in 1923 – North Midlothian and Berwick & Haddington.

That meant in the space of two elections Labour went from holding just one of the 10 Lothian seats to holding five. Over the same period, Liberal numbers remained steady while the Unionists went from five to one.

Judging by the detailed reports of election meetings in the Evening News, the 1923 campaign in Edinburgh focused mainly on the consequences of the Tories' plans for import tariffs. On the day parliament was dissolved for the election, November 16, 1923, the Evening News sided with the Liberals, attacking the Tories’ "moth-eaten scheme of trade restriction" and adding that "tariff reform will be detrimental to the Port of Leith".

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdVivian Phillipps, the Liberal chief whip who was seeking re-election as MP for Edinburgh opened his campaign at the Gorgie War Memorial Hall, describing the election as a "housewives' battle". He predicted tariffs would mean the return of the shortages of goods which had been experienced during the war.

At another meeting, Morris Mancor, the Unionist candidate in Edinburgh East, conceded that tariffs would mean tinned foods would cost more, but added: "We would be a healthier nation today if we ate less tinned food."

Mancor was also at the centre of controversy because although he was standing as a Unionist he had been elected as a councillor three years earlier with Liberal backing and he was still a member of the Canongate Liberal Association. He defended his position, saying he had been elected to the council with backing from both parties and made clear he would not tie himself to either. He also argued there was no Unionist association in the ward and he wanted to support the social work done by the Liberal association.

And as chair of the counci's tramways committee he was accused of having voted in favour of German steel rails. He said he had been putting forward the views of the committee.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese were the days when each party held its own meetings and was able to draw large numbers – the Evening News reported that Willie Graham's opening rally for Labour in Central attracted 700 in the Buccleuch Church Hall, but 300 more were turned away because there was no overflow hall.

But hecklers and “organised rowdyism” were a regular feature and things could get heated, prompting headlines like “Wild Night at Abbeyhill”, “Canongate Uproar” and ”Police to the Rescue at Lauriston”.

In an apparently radical move, the Liberal candidate in Edinburgh North, Wilson Raffan – who would go on to win the seat – suggested a joint meeting "at which both sides would be presented". But his Unionist opponent Patrick Ford dismissed the idea, saying these were “the methods of the hustings" which he declared "obsolete".

At one point Ford also threatened legal action against Raffan, alleging a Liberal canvasser had claimed Ford wanted to take away the old age pension.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere were rumours of a deal in which the Liberals would give Labour a free run in Central if Labour did not put up a candidate against the Liberals in West, but in the end the two parties each fought both seats.

Former prime minister David Lloyd George made a brief campaign stop in Edinburgh on his way by train from Glasgow to Newcastle, taking "a few minutes" to address a crowd at Waverley station. A sprig of white heather was placed in his buttonhaole and he climbed onto a luggage trolley to denounce the Tories' "ill-thought-out, hasty and dangerous" tariff proposals. And he declared the election "the most momentous contest for many a year" – the life of the country, its trade, its commerce, its livelihood depended on it."

The counting of votes in Edinburgh, as in most of the country, did not take place until the day after polling day. The results across Lothian showed two gains for Labour and one for the Liberals. In North Midlothian, centred on Dalkeith, the Labour candidate, miners' union official Andrew Clarke, who had failed by just 474 votes to take the seat in 1922, won with a 1,839 majority.

In Berwick & Haddington, Clydebank engineer Robert Spence had come within 500 votes of winning the seat for Labour in 1922, but lost to National Liberal Walter Waring in a four-cornered fight. In 1923, Spence won by just 68 votes, with the Unionist candidate, Boer War veteran Chichester Crookshank, in second place and Waring third.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd in Edinburgh West, Liberal Wilson Raffan, who had previously served as a Lancashire MP, won a 2,835 majority, ousting Unionist Patrick Ford, thanks on an impressive 17.5 per cent swing. He noted that five of the six MPs Edinburgh had elected were supporters of free trade and declared: “Edinburgh will be a light for all the rest of the land."

When parliament met in January, Baldwin and his Conservatives were duly defeated on the programme they put forward in the King’s Speech and George V sent for Labour’s Ramsay MacDonald to become prime minister. Willie Graham, who had nearly doubled his majority in Edinburgh Central, was made Financial Secretary to the Treasury, effectively deputy to the Chancellor, Philip Snowden.

It was a historic moment for all involved. But the jubilant new Labour MPs could not escape immediate practicalities. There was a rail dispute – how were they to get home from London? The Evening News reported: “Some of them feared that they might be accused of using blackleg labour on the railways if they went by train.” But there was a solution not readily available nowadays: “The Scottish Labour contingent made enquiries, as the result of which they provisionally arranged to sail tonight from London to Leith.”